This blog looks at two major painting styles: figurative and abstract. One shows the visible world, the other uses form and color to express ideas. We outline their definitions, history, techniques, and viewer response.

Definition:

Figurative painting: It’s art that reflects the observable world: people, places, or objects, using believable proportions and light so our brains say, “Yep, I know what that is.”

Why it matters: We read the scene almost like a film still. Because we recognize the subject, our attention shifts quickly to how it’s presented: the sitter’s expression, the lighting, the setting, the implied story.

Abstract painting: It’s art that steps away from literal depiction. Instead of showing a thing, it orchestrates color, shape, and movement to create a mood or idea.

Why it matters: With no obvious subject to “solve,” viewers rely on gut reaction memories, emotions, even physical sensations. It’s less about reading and more about feeling.

A Brief History of Figurative and Abstract Art

Figurative art has always been rooted in representing the visible world. It focuses on recognizable people, places, and objects, even as styles and techniques evolve. From the highly realistic paintings of the Renaissance, where artists aimed to capture the human form and perspective with precision, to modern interpretations like glitch-portraits that digitally distort faces or scenes, figurative art stretches and experiments.

But no matter how abstracted or stylized it becomes, it maintains a visual connection to reality. That connection is what defines it. It may bend or reinterpret, but it never fully breaks away from what we can identify or relate to in the real world.

Abstract art, on the other hand, marked a major shift in the early 20th century when artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian began to move away from direct representation. They focused instead on the emotional or spiritual qualities of color, shape, and line.

The goal was not to depict the world as it appears, but to express ideas, moods, or inner states through purely visual language. Over time, abstraction has expanded to include digital and conceptual practices, such as algorithm-based compositions or artworks generated using artificial intelligence. These works often prioritize structure, pattern, and sensation over narrative or realism, fully detaching from recognizable subjects in favor of visual or experiential impact.

Visual Elements and Techniques

|

Element |

Figurative Use |

Abstract Use |

|

Line |

Draws clear outlines, shows depth, maps body parts. |

Shows motion, energy, or rhythm with fast or repeated strokes. |

|

Colour |

Matches real-life colours and light, makes skin look warm or cool. |

Uses bright or unexpected colours to spark emotion or eye-buzz. |

|

Composition |

Puts a main subject in a strong spot, leads the viewer through front and back space. |

Spreads shapes across the whole canvas, often off-balance to add tension. |

|

Surface |

Keeps paint smooth or slightly textured so the scene stays believable. |

Lets paint drip, pool, or build up in rough layers so the texture becomes the star. |

|

Media |

Traditional oil, acrylic, pencil, or digital brushes that imitate them. |

Spray paint, house paint, collage bits, or computer code that prints its own patterns. |

Figurative vs. Abstract: How We Perceive

|

Factor |

Figurative Effect |

Abstract Effect |

|

Initial entry |

The viewer quickly recognizes people, objects, or settings. This makes the artwork easier to engage with right away. |

The viewer is drawn in through curiosity. They often spend more time exploring patterns, shapes, or colors to make sense of what they see. |

|

Cognitive load |

The brain works to decode visual storytelling. It tries to understand characters, actions, or emotional cues, creating empathy and narrative involvement. |

The mind is more open-ended here. It focuses on mood, visual rhythm, or symbolism. This encourages introspection or calm attention rather than storytelling. |

|

Memory trace |

The image is remembered as a specific scene or moment, like a mental snapshot. |

The memory left is more emotional or atmospheric. It feels like recalling a mood through a blend of colors or shapes rather than a clear image. |

Examples of Figurative and Abstract Art

Figurative Art:

1. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, 1503

Soft modeling and subtle expression create psychological depth and lifelike presence.

2. Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656

Complex composition blending realism with a self-aware gaze on the act of painting.

Abstract Art:

1. Mark Rothko, Untitled (Black on Grey), 1970

Large color fields evoke emotional stillness and existential depth.

2. Sarah Sze, Triple Point (Pendulum), 2013

Fragmented, immersive installation blending abstraction, science, and sensation.

Figurative vs Abstract Sculpture - What's The Difference?

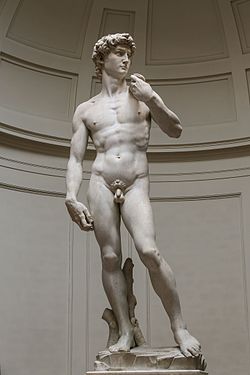

The difference between figurative and abstract becomes physical. Figurative sculpture connects us to recognizable bodies or objects, while abstract sculpture focuses on shape, material, and spatial sensation rather than likeness. Both approaches shape meaning, but they do it through different kinds of presence and interaction.

Key Differences Between Figurative and Abstract Sculpture

| Aspect | Figurative Sculpture | Abstract Sculpture |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Reference | Represents real subjects such as humans, animals, or objects | Removes recognizable subjects and focuses on pure form |

| Goal | To show believable anatomy, gesture, and physical presence | To explore ideas, emotions, or spatial concepts through shape and material |

| Viewer Entry Point | Starts with recognition and identification | Starts with curiosity and feeling |

| Use of Materials | Uses materials to imitate real textures like skin, fabric, fur, or movement | Uses materials for their inherent qualities such as weight, tension, shine, or roughness |

| Interaction With Space | Reads as a contained object with clear front, back, and profile views | Often activates the surrounding space, blurring object and environment |

| Emotional Effect | Encourages empathy and narrative, as if meeting a presence | Encourages mood, atmosphere, or contemplation |

| Movement Suggested | Based on natural poses or actions | Based on rhythm, flow, balance, or imbalance of forms |

Examples of Figurative Sculpture

Figurative sculpture has shaped our understanding of the human body, gesture, and presence for centuries. The following examples show how different artists capture realism, emotion, and physicality across time.

1. Michelangelo, David, 1504

A study of human tension and focus, transforming marble into living presence.

2. Auguste Rodin, The Walking Man, 1907

Raw gesture and motion communicate humanity through incomplete but expressive form.

Examples of Abstract Sculpture

Abstract sculpture opens the door to form, space, and sensation without relying on recognizable subjects. These examples highlight how artists use shape, material, and movement to create meaning beyond representation.

1. Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1923

A pure exploration of motion reduced to a single vertical glide.

2. Barbara Hepworth, Sphere with Inner Form, 1963

Smooth curves and hollowed space create a calm, contemplative experience.

Closing Note

While figurative and abstract art take different paths, one rooted in recognition and the other in sensation, they both invite us to look more closely and feel more deeply. Understanding how each speaks opens up richer ways of seeing and turns viewing into an active exchange between artist and audience. In the end, both modes expand not just how we interpret art but also how we interpret the world.